Registered on the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage List as part of the “Yama, Hoko, Yatai, float festivals in Japan,” the Furukawa Festival is a nationally renowned annual event of the Ketawakamiya Shrine, which overlooks the town from an elevated location. It is also a traditional Shinto ritual that has been designated as National Important Intangible Folk Cultural Properties. The festival consists of three groups of events: the core mikoshi (portable shrine) procession, which is a stately traditional Shinto ritual, combined with the two major events of the dynamic Okoshi-Daiko (rousing drum) and the tranquil yatai float parade. Each year, it is held over two days on April 19th and 20th, drawing a large crowd.

In the Hida region, festivals do not take the form of people visiting shrines. Once a year, the spirit of the deity, in which the clan’s ancestor worshipped as a deity and the local guardian deity are united, is led from the shrine situated on a mountain to the town of shrine parishioners, who make offerings and pray to it. These are central to the festival events.

In the main hall of the Ketawakamiya Shrine, a rite is solemnly observed to place the deity in the mikoshi, with the sound of portable gongs beaten by the Tokeiraku (cockfighting music) performers resonating. Meanwhile, to prepare for welcoming the mikoshi, the yatai floats are paraded around in respective neighborhoods. Then, the mikoshi is borne through the town in a procession attended by the performers of kagura (Shinto music), gagaku (court music), Tokeiraku, and Shishimai (lion dance), as well as Taimeiki (yatai name banners) taking on the role of the yatai floats that used to be at the forefront of the procession. Once the mikoshi arrives and is enshrined at Otabisho (a place in the town where the deity can stay) in the evening, the place is guarded throughout the night.

In the morning, all the yatai floats are gathered and lined up in front of Otabisho, then moved to the predetermined place and lined up there again. Over the course of this process, they also serve as stages for playing music and performing arts, including karakuri ningyo (mechanical marionettes) and children’s Kabuki. In the meantime, the mikoshi is borne through the town and returned to the Ketawakamiya Shrine. At dusk, the yatai floats of all neighborhoods are lined up at the predetermined place and paraded in procession throughout the town during the Yomatsuri event.

On the night of April 19th, half-naked men carry around a frame-mounted turret on which a large drum is perched, bumping into each other and making the rounds of the town. The origin of the Okoshi-Daiko is said to be the “wake-up drums” that announce the start of the festival, which has evolved into the current form with the passage of time.

The Okoshi-Daiko is led by an ethereally beautiful lantern procession in which females, children, and even out-of-towners march throughout the town holding paper lanterns, whether large ones on poles or small round ones. What follows this procession is a main attraction of the festival, the Okoshi-Daiko.

The Okoshi-Daiko event begins with several hundred men singing a celebratory song in chorus at the Uchidashi (drum-beating kickoff) ceremony held in the Matsuri Hiroba square. Immediately after that, a frame-mounted turret on which a large drum is perched starts to move, followed by teams representing each neighborhood, carrying small drums called Tsuke-Daiko. The greatest glory for these teams being for their Tsuke-Daiko to gain the position nearest the turret with the large drum, a mad scramble continues until around midnight as teams vie for that honor. Another must-see is the “tombo” stunt, which is performed by members of these teams using a pole to which Tsuke-Daiko is attached, with one climbing to the top of the pole approximately 3.5 meters high.

The main role of beating the large drum on the turret is a once-in-a-lifetime honor and what every shrine parishioner yearns for. The young men chosen for this role spend more than a month polishing and creating the wooden sticks used in striking the drum, made from willow branches they themselves have gone to the mountains and cut. As they beat the drum with heartfelt devotion, its deep sound stirs the soul.

In Furukawa, the floats used in the festival are called “yatai.” Besides being paraded through the town, they are used as stages for performing arts, including karakuri ningyo and children’s Kabuki.

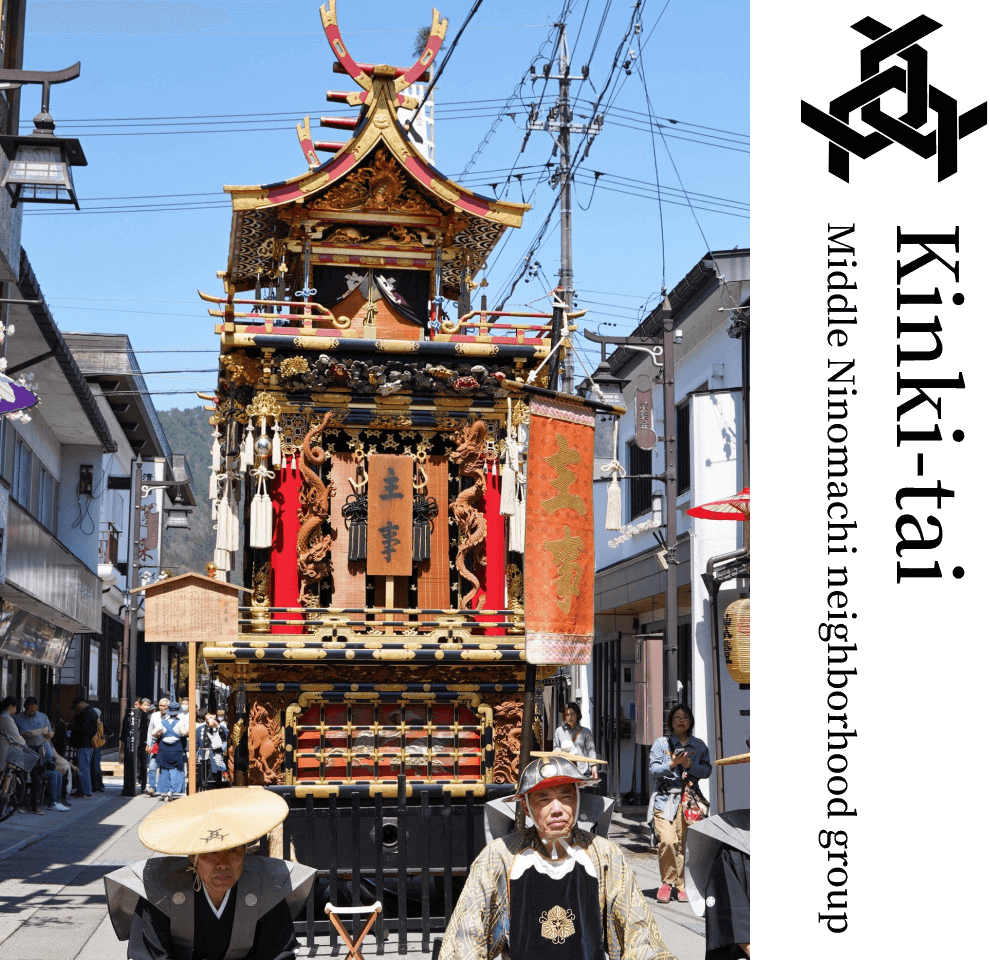

When the first yatai was created is uncertain; but according to the earliest record remaining, a yatai known as Kinki-tai was built in 1776, during the Edo period, by the Middle Ninomachi neighborhood group.

The yatai of the Furukawa Festival can be seen as resulting from the fusion of the cultures of Eastern and Western Japan. The yatai brought in from Edo were enhanced by the craftsmen of Hida, and with the addition of karakuri ningyo from Kyoto evolved into a distinctive form. They further incorporated the art of lacquer painters, and even the metal fixtures and textiles of Kyoto, resulting in the elaborately decorated floats of today. Currently, there are 10 yatai floats including a disused one in Furukawa, all of which are carefully stored and preserved as treasures of each neighborhood. Three of the yatai actually used in the festival are on display in the Hida Furukawa Festival Exhibition Hall year-round.

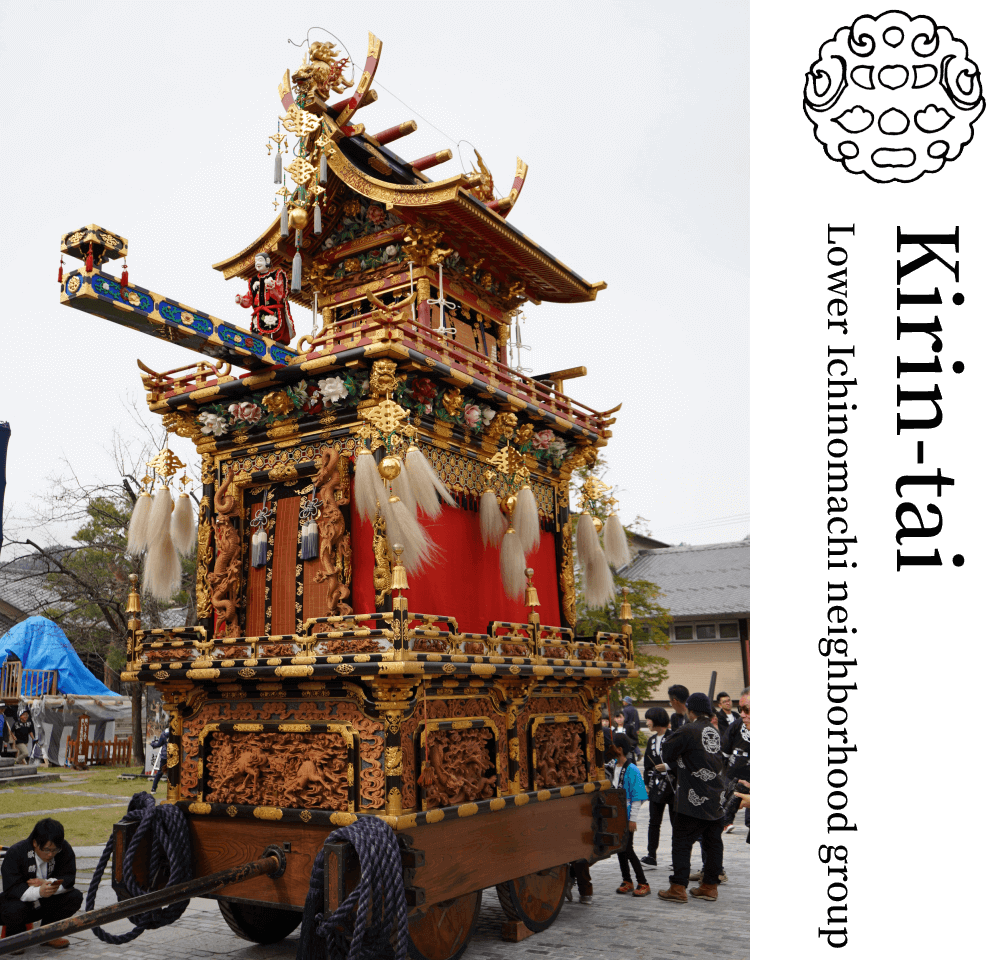

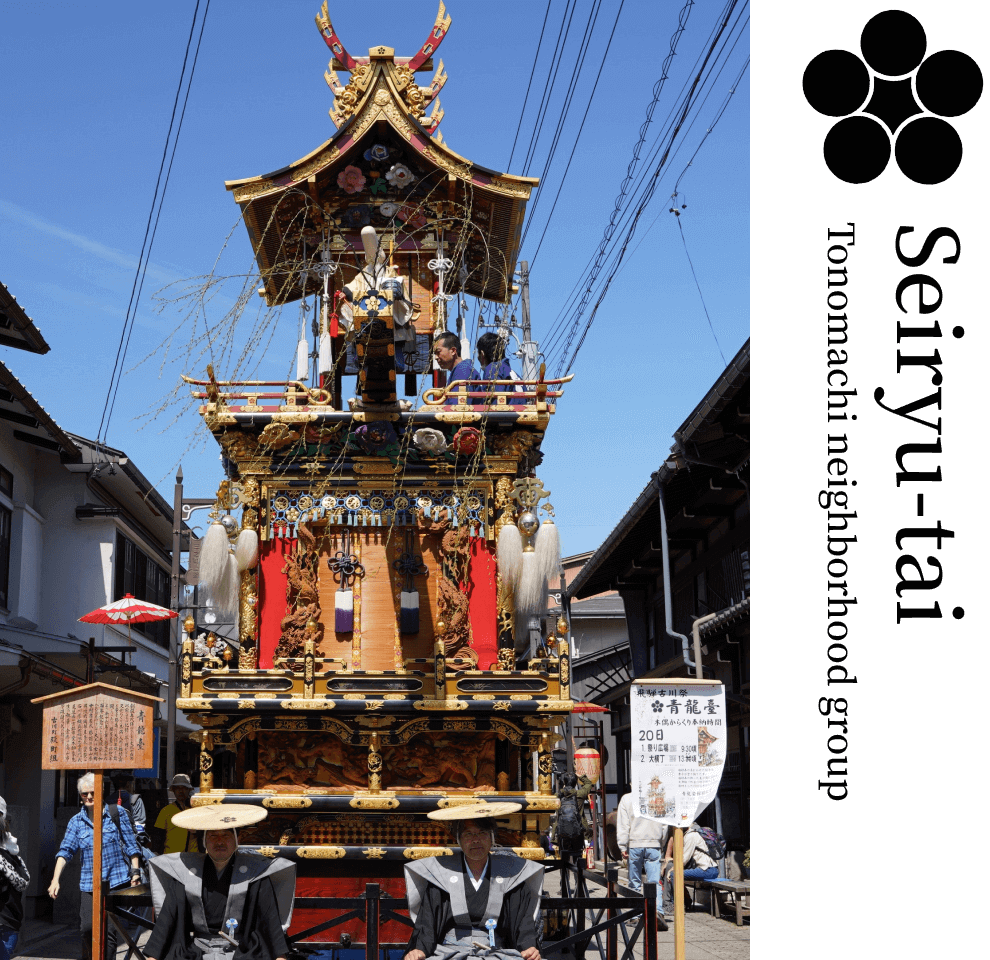

On April 19th, the 10 yatai floats are taken out of their respective warehouses and paraded in each neighborhood. On the following 20th, they are lined up in the predetermined places. Then, at various intersections of the town, mechanical marionettes perform on two floats, the Seiryu-tai and Kirin-tai, while children’s Kabuki is played on the Byakko-tai float, as if a magnificent historical picture scroll unfolded.

Yomatsuri, an event concluding the Furukawa Festival, is held on the night of April 20th. Each yatai float is paraded with its paper lanterns lit, announcing the end of the festival throughout the town. The yatai floats illuminated by swinging small lanterns create an ambience of quiet and elegant beauty in contrast to its daytime liveliness.

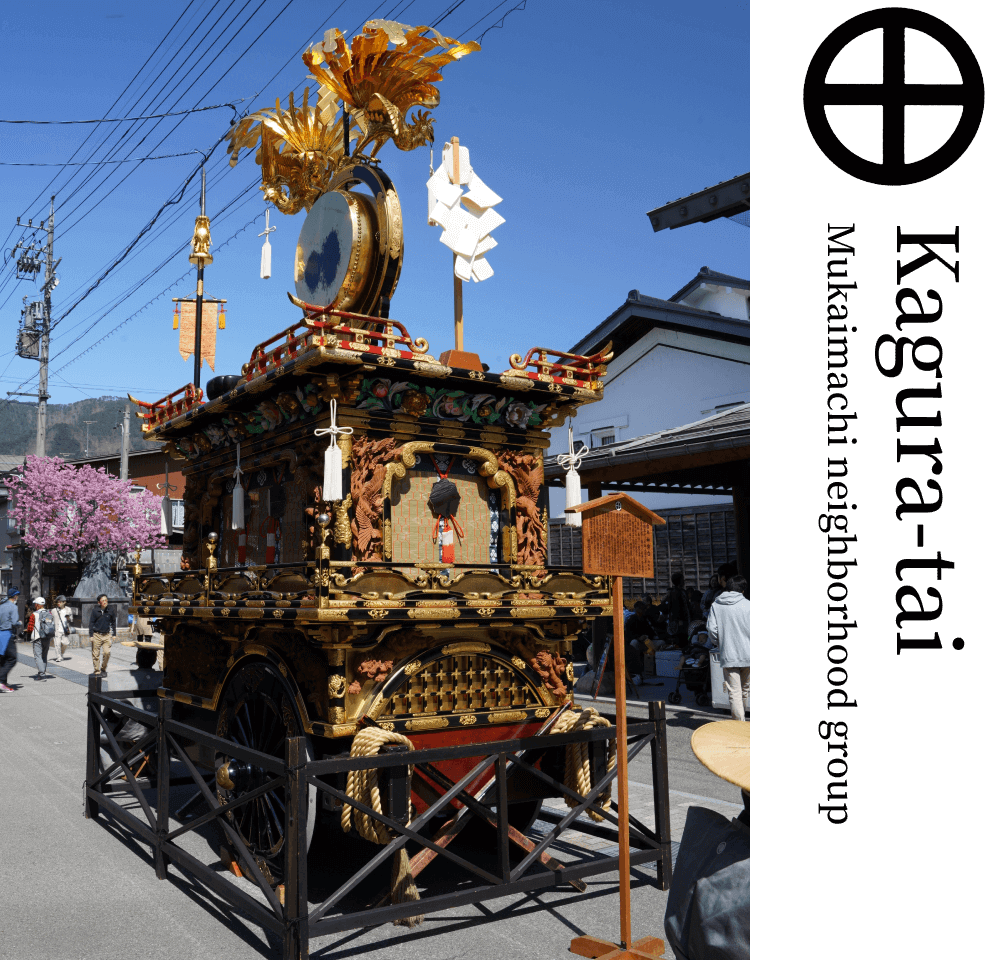

In the morning when the festival begins, the deity enshrined in the Ketawakamiya Shrine is placed at the front of the upper level of this yatai, along with a gohei purifying streamer. Of all the Furukawa yatai floats, this is the only roofless one. With a gold-colored large drum hung atop, the Kagura-tai leads the yatai procession while two shishi (lions) dance in tune with the kagura music rendered by five performers, each wearing the traditional eboshi hat and hitatare dress. This yatai is unique in that it is a three-wheeler, running on two large outer wheels plus one inner wheel. In addition, each time the drummer beats the large drum on which golden phoenixes perch, he arches backward—that is a sight to behold.

The original Edo-period yatai, disused since 1891, was rebuilt in 1922. A masterpiece representing the Taisho era in which it was completed, the yatai catches spectators’ eyes with two large golden Ho’o (phoenixes) perching at the front and back of the roof, true to the yatai name. The lower level is adorned with two dragon-themed carvings as if they were competing with each other: one is a work of the first Gunho Murayama; and the other was made by Goun Oshima of the Inami district in the Ecchu region. The metal netting protecting these carvings has been skillfully made by welding each wire by hand.

Miokuri: Gyokujun Hasegawa, Ho’o hibu no zu (A soaring phoenix), 1922.

While when it was originally built is unknown, the present yatai was completed in 1933 after nine years of work. Operated on this yatai is a mechanical marionette clad in traditional Chinese attire, which joyously dances wearing a lion mask when flowers bloom in the basket it carries. The 12 signs of the Chinese zodiac are engraved on the side panels in the middle level. It may be fun to find your own sign there.

Miokuri: Seison Maeda, Fujin raijin zu (Wind and thunder gods), 1952.

Alternative Miokuri: Shunki Tamaya, Yamatotakerunomikoto tosei zu (Prince Yamatotakeru’s eastern Japan expedition), 1933.

A remaining record shows that the original Kinki-tai was constructed in 1776, which seems to be the oldest yatai built in Furukawa. Of the present Furukawa yatai floats, too, the Kinki-tai rebuilt in 1841 is the oldest. The delightful turtles are seen all over this yatai, whether metal fixtures, carvings, or embroideries, reflecting the vivid imagination of people in the olden days.

Miokuri: Soryuzu (Two dragons), a Gobelin woven with pure gold threads in India, 1841.

Alternative Miokuri: Shonen Suzuki, Kijo Urashima no zu (Urashima on a turtle), 1910.

Completed in 1886, this is the largest yatai in Furukawa, with highly eye-catching carvings of large dragons ascending and descending. Another dragon-themed carving in the lower level was rendered by Torakichi Shimizu of the Suwa district in the Shinano region, indicating the close ties between that region and Furukawa at the time when the yatai was built. With children spinning tops, flying kites, and playing other traditional games engraved in detail on the side panels in the middle level, this yatai is a joy to behold too.

Miokuri: Unrin Kaito, Unryuzu (A dragon among the clouds), 1886.

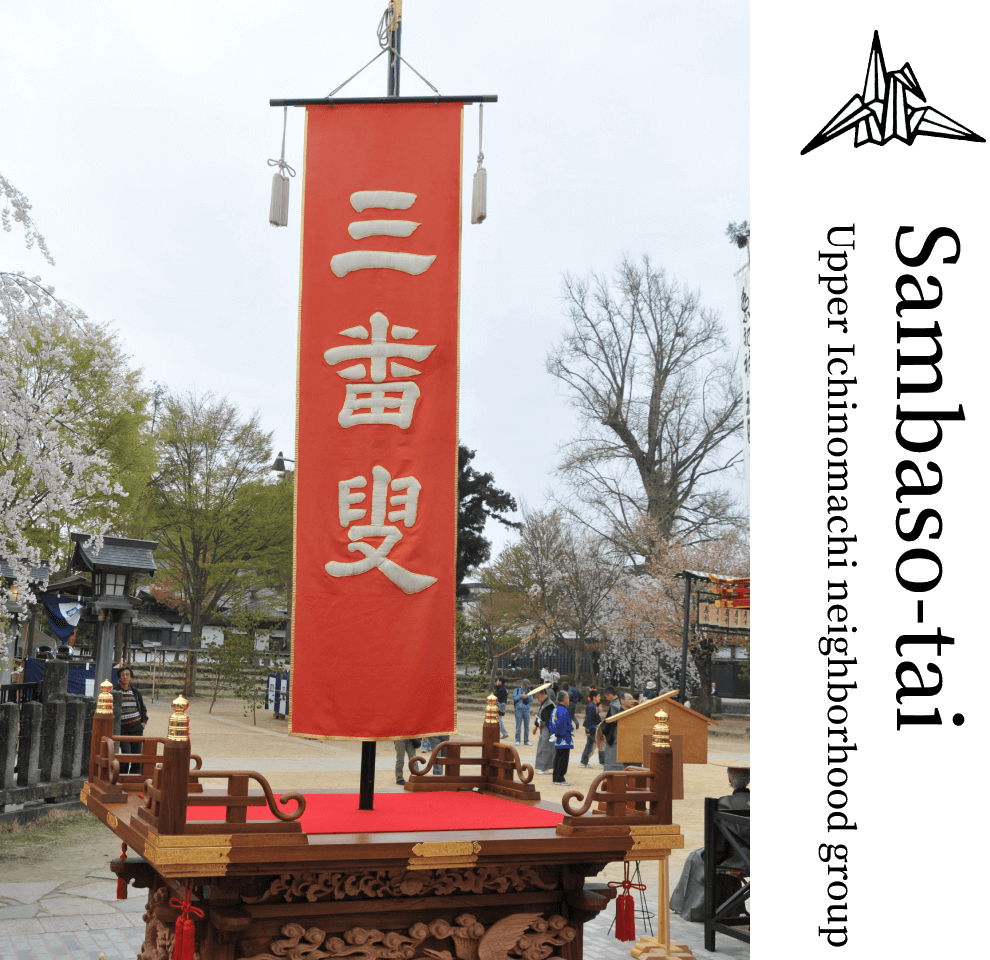

Named after sanko (three lights)—the sun, the moon, and a star—this yatai was completed in 1862, designed by townsman Rihachi Hachiya and built by renowned craftsman Shunko Ishida. A relatively small yatai, the Sanko-tai perfectly blends with the compact townscape, described as the best representation of the characteristics of the Furukawa yatai floats. Goun Oshima, a master engraver of the Inami district in the Ecchu region, beautifully carved a lion with a peony and embossed wickerwork and lion-crest patterns.

Miokuri: Bairei Kono, Susanoonomikoto yamata no orochi taiji no zu (Prince Susanoo eliminating an eight-headed snake), 1888.

Alternative Miokuri: Baisai Matsumura, Torazu (A tiger), 1862.

Originally created in 1816 and renovated a number of times, the Seiyo-tai of today was completed by carpenter Hikojiro Kamitani in 1941 after eight years of work. The yatai boasts the magnificent carving of peonies and leaves in the middle level, made by Rihachi Hachiya out of a single wooden piece. The word “seiyo” means shining purely. True to its name, the yatai is gorgeous yet exudes a sense of purity.

Miokuri: Keisho Imao, Kaihin oimatsu zu (Ancient pines on a beach), 1946.

The Byakko-tai of today is the result of a three-year project from 1981 to completely renovate the original yatai completed in 1842. Decked with the Yoshitsune Minamoto samurai doll at the front of the upper level, the yatai provides in the middle level a stage for children performing a Kabuki play titled Hashi Benkei (Benkei on the bridge) in a magnificent yet adorable manner. The Byakko-tai is a highly precious yatai because it is the only one that preserves the ancient yatai format, such as having little carvings, metal fixtures, and other adornments, and securing enough headroom in the lower level for people to get on and off the yatai without stooping.

Adopting the Umebachi insignia that is the crest of the Kanamori family, this yatai is elegantly and gracefully adorned with the black and gilt lacquer wheels. It also boasts the splendid peonies and lions that are carved out of a thousand-year-old zelkova. The marionettes operated in tune with the Noh song Tsurukame (Crane and turtle) perform a story inspired by a drawing in the Otsu region titled “Gehono hashigozori” (Climbing a ladder to shave a long head). The marionettists skillfully manipulate the strings as a marionette clad in traditional Chinese attire climbs a ladder that stands against the shoulder of Fukurokuju—the god of happiness, wealth, and longevity—and a turtle turning into a crane.

Miokuri: Insho Domoto, Shotenryu (A dragon ascending to heaven), 1940.

This yatai has been disused due to the 1904 great fire in Furukawa. All that remains from that time is the Onna Sambaso (female Sambaso) mechanical marionette and the Shojohi (scarlet) large curtain.

The Shishimai teams performing at the Furukawa Festival belong to either the Miyamoto group of Kamikita or the Kagura-tai group, both dancing accompanied by flutes and drums. The Miyamoto group’s Shishimai team consists of five lions, which first perform upon departure of mikoshi in the open space below the Ketawakamiya Shrine’s hall of worship, thereafter accompanying the mikoshi procession throughout the festival. On the other hand, the Kagura-tai’s Shishimai goes with the yatai all the way.

The portable gongs and small drums are used in performing song and dance music for soothing and consoling the deity with their sounds. Dozens of youth and middle- and elementary-schoolers playing the Tokeiraku join in the mikoshi procession dressed in their traditional patterned attire, and at times break out in dancing throughout the town. Tokeiraku is familiarly known as “Kankakokan,” onomatopoeia expressing the high-pitched inharmonic tones and rhythmic music. Each Tokeiraku performer wears an ichimongasa bamboo hat with a white kimono dyed with red and navy phoenixes and dragons.

Each neighborhood sets up a temporary center for inviting and making offerings to the deity. These centers also serve as meeting places for deliberating annual festival matters relating to the yatai groups, administration, and finances as well as fulfilling these functions. In an altar inside the meeting place, white paper strips are placed on the top shelf, and offerings such as rice, sacred sake, and fruits of the sea and mountains are made. In front of the altar are lined many bottles of sake from the shrine parishioners. On the two days of the Furukawa Festival alone, approximately 10,000 bottles of sake are said to be offered.

When alerted that the mikoshi procession is nearing, the townspeople first spread lines of salt in the middle of the road along the mikoshi route, creating and purifying a path for it; then, sprinkle a line of salt in front of their homes, drawing branch segments from the main line to their entranceway, enticing the sacred presence of the deity into their homes. In the past, red soil taken from mountains was distributed to each town household for that purpose. However, when the road was asphalted, salt replaced the red soil that made the road muddy and slippery.

The custom of Yobihiki—inviting and entertaining relatives and friends to participate in a lavish feast with sake in your home—is a culture born of the Furukawa Festival that has taken root in the area. Guests are treated to elaborate homemade dishes using ingredients from the land, river, and sea, such as rice and vegetables locally grown in Hida and fish from the Toyama Bay. Hida’s local custom dictates that until the celebratory song ends, banquet attendants not leave their seats to pour sake for others. The people of Hida have honored this rule to this day.

The men of Hida are warmhearted, passionate, and earnest, never giving up once their minds are made up. They underpin the town of Furukawa, harnessing the sense of community created through the festival. Just as the Furukawa Festival offers two contrasting atmospheres, dynamic and tranquil, these men are energetic yet sensitive. The term “Furukawa Yancha” describes such an attractive temperament they have.